HMS Rodney (29) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

HMS ''Rodney'' was one of two s built for the

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

in the mid-1920s. The ship entered service in 1928, and spent her peacetime career with the Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe an ...

and Home Fleet

The Home Fleet was a fleet of the Royal Navy that operated from the United Kingdom's territorial waters from 1902 with intervals until 1967. In 1967, it was merged with the Mediterranean Fleet creating the new Western Fleet.

Before the First ...

s, sometimes serving as a flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the fi ...

when her sister ship

A sister ship is a ship of the same class or of virtually identical design to another ship. Such vessels share a nearly identical hull and superstructure layout, similar size, and roughly comparable features and equipment. They often share a ...

, , was being refitted. During the early stages of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, she searched for German commerce raider

Commerce raiding (french: guerre de course, "war of the chase"; german: Handelskrieg, "trade war") is a form of naval warfare used to destroy or disrupt logistics of the enemy on the open sea by attacking its merchant shipping, rather than enga ...

s, participated in the Norwegian Campaign, and escorted convoys in the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

. ''Rodney'' played a major role in the sinking of the German battleship ''Bismarck'' in mid-1941.

After a brief refit in the United States, she escorted convoys to Malta and supported the Allied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

invasion of French Algeria

French Algeria (french: Alger to 1839, then afterwards; unofficially , ar, الجزائر المستعمرة), also known as Colonial Algeria, was the period of French colonisation of Algeria. French rule in the region began in 1830 with the ...

during Operation Torch

Operation Torch (8 November 1942 – Run for Tunis, 16 November 1942) was an Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of French North Africa during the Second World War. Torch was a compromise operation that met the British objective of secu ...

in late 1942. The ship covered

Cover or covers may refer to:

Packaging

* Another name for a lid

* Cover (philately), generic term for envelope or package

* Album cover, the front of the packaging

* Book cover or magazine cover

** Book design

** Back cover copy, part of co ...

the invasions of Sicily (Operation Husky

Operation or Operations may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* ''Operation'' (game), a battery-operated board game that challenges dexterity

* Operation (music), a term used in musical set theory

* ''Operations'' (magazine), Multi-Man ...

) and Italy (Operation Baytown

Operation Baytown was an Allied amphibious landing on the mainland of Italy that took place on 3 September 1943, part of the Allied invasion of Italy, itself part of the Italian Campaign, during the Second World War.

Planning

The attack was ...

) in mid-1943. During the Normandy landings

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on Tuesday, 6 June 1944 of the Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during World War II. Codenamed Operation Neptune and often referred to as ...

in June 1944, ''Rodney'' provided naval gunfire support

Naval gunfire support (NGFS) (also known as shore bombardment) is the use of naval artillery to provide fire support for amphibious assault and other troops operating within their range. NGFS is one of a number of disciplines encompassed by th ...

and continued to do so for several following offensives near the French city of Caen

Caen (, ; nrf, Kaem) is a commune in northwestern France. It is the prefecture of the department of Calvados. The city proper has 105,512 inhabitants (), while its functional urban area has 470,000,convoy through the Arctic to the

The ''Nelson''-class battleship was essentially a smaller, battleship version of the

The ''Nelson''-class battleship was essentially a smaller, battleship version of the

The

The

The high-angle directors and rangefinder and their platform were replaced by a new circular platform for the

The high-angle directors and rangefinder and their platform were replaced by a new circular platform for the  During a brief refit in HM Dockyard, Rosyth, Scotland, from 24 August to 10 September 1940, the Type 79Y radar was upgraded to a Type 279 system and two Oerlikon light

During a brief refit in HM Dockyard, Rosyth, Scotland, from 24 August to 10 September 1940, the Type 79Y radar was upgraded to a Type 279 system and two Oerlikon light

''Rodney'', named for

''Rodney'', named for

With ''Nelson'' damaged by a mine on 4 December, ''Rodney'' served as the temporary fleet flagship until her sister's return in August. She mostly spent January and February 1940 at anchor with occasional missions to provide cover from commerce raiders for convoys. During one such sortie on 21 February in heavy weather, her steering problems resurfaced and forced her return to

With ''Nelson'' damaged by a mine on 4 December, ''Rodney'' served as the temporary fleet flagship until her sister's return in August. She mostly spent January and February 1940 at anchor with occasional missions to provide cover from commerce raiders for convoys. During one such sortie on 21 February in heavy weather, her steering problems resurfaced and forced her return to

''Bismarck'' was spotted by a RAF

''Bismarck'' was spotted by a RAF

She departed Scapa on 2 August with orders for convoy escort duties, but was soon diverted to become part of the close escort for Convoy WS 21S, bound for Malta as part of Operation Pedestal. Vice-Admiral Sir Bruce Fraser, second-in-command of the Home Fleet, was aboard the ship to gain experience in integrating carrier and convoy operations and was not flying his flag. ''Rodney'' rendezvoused with the convoy two days later and was assigned to Force Z which would turn back before the convoy passed through the Sicilian Narrows. Italian spies in

She departed Scapa on 2 August with orders for convoy escort duties, but was soon diverted to become part of the close escort for Convoy WS 21S, bound for Malta as part of Operation Pedestal. Vice-Admiral Sir Bruce Fraser, second-in-command of the Home Fleet, was aboard the ship to gain experience in integrating carrier and convoy operations and was not flying his flag. ''Rodney'' rendezvoused with the convoy two days later and was assigned to Force Z which would turn back before the convoy passed through the Sicilian Narrows. Italian spies in  Force H was to provide distant cover for the landings at

Force H was to provide distant cover for the landings at

The ship departed Scapa on 16 January 1944 to begin repairs in Rosyth. Little effort was made to repair the persistent steering and boiler problems as efforts focused on making her seaworthy again. They were completed on 28 March, and ''Rodney'' steamed back to Scapa, where she arrived on 1 April. The ship spent most of the next few months conducting gunnery training, mostly shore bombardment but also anti-aircraft shoots and practice defending herself against attacks by

The ship departed Scapa on 16 January 1944 to begin repairs in Rosyth. Little effort was made to repair the persistent steering and boiler problems as efforts focused on making her seaworthy again. They were completed on 28 March, and ''Rodney'' steamed back to Scapa, where she arrived on 1 April. The ship spent most of the next few months conducting gunnery training, mostly shore bombardment but also anti-aircraft shoots and practice defending herself against attacks by

Maritimequest HMS ''Rodney'' Photo Gallery

{{DEFAULTSORT:Rodney (1925) Nelson-class battleships Ships built on the River Mersey 1925 ships World War II battleships of the United Kingdom

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

in late 1944. In poor condition from extremely heavy use and a lack of refits, she was reduced to reserve

Reserve or reserves may refer to:

Places

* Reserve, Kansas, a US city

* Reserve, Louisiana, a census-designated place in St. John the Baptist Parish

* Reserve, Montana, a census-designated place in Sheridan County

* Reserve, New Mexico, a US vi ...

in late 1945 and was scrapped

Scrap consists of recyclable materials, usually metals, left over from product manufacturing and consumption, such as parts of vehicles, building supplies, and surplus materials. Unlike waste, scrap has monetary value, especially recovered me ...

in 1948.

Background and description

The ''Nelson''-class battleship was essentially a smaller, battleship version of the

The ''Nelson''-class battleship was essentially a smaller, battleship version of the G3 battlecruiser

The G3 battlecruisers were a class of battlecruisers planned by the Royal Navy after the end of World War I in response to naval expansion programmes by the United States and Japan. The four ships of this class would have been larger, faster ...

which had been cancelled for exceeding the constraints of the 1922 Washington Naval Treaty

The Washington Naval Treaty, also known as the Five-Power Treaty, was a treaty signed during 1922 among the major Allies of World War I, which agreed to prevent an arms race by limiting naval construction. It was negotiated at the Washington Nav ...

. The design, which had been approved six months after the treaty was signed, had a main armament of guns to match the firepower of the American and Japanese es in the battleline

The line of battle is a tactic in naval warfare in which a fleet of ships forms a line end to end. The first example of its use as a tactic is disputed—it has been variously claimed for dates ranging from 1502 to 1652. Line-of-battle tacti ...

in a ship displacing no more than .Raven & Roberts, p. 109

''Rodney'' had a length between perpendiculars

Length between perpendiculars (often abbreviated as p/p, p.p., pp, LPP, LBP or Length BPP) is the length of a ship along the summer load line from the forward surface of the stem, or main bow perpendicular member, to the after surface of the ster ...

of and an overall length

The overall length (OAL) of an ammunition cartridge is a measurement from the base of the brass shell casing to the tip of the bullet, seated into the brass casing. Cartridge overall length, or "COL", is important to safe functioning of reloads i ...

of , a beam

Beam may refer to:

Streams of particles or energy

*Light beam, or beam of light, a directional projection of light energy

**Laser beam

*Particle beam, a stream of charged or neutral particles

**Charged particle beam, a spatially localized grou ...

of , and a draught of at standard load

The displacement or displacement tonnage of a ship is its weight. As the term indicates, it is measured indirectly, using Archimedes' principle, by first calculating the volume of water displaced by the ship, then converting that value into wei ...

. She displaced at standard load and at deep load

The displacement or displacement tonnage of a ship is its weight. As the term indicates, it is measured indirectly, using Archimedes' principle, by first calculating the volume of water displaced by the ship, then converting that value into wei ...

. Her crew numbered 1,361 officers and ratings when serving as a flagship and 1,314 as a private ship

Private ship is a term used in the Royal Navy to describe that status of a commissioned warship in active service that is not currently serving as the flagship of a flag officer (i.e., an admiral or commodore

Commodore may refer to:

Ranks

* C ...

.Burt, p. 348 The ship was powered by two sets of Brown-Curtis geared steam turbine

A steam turbine is a machine that extracts thermal energy from pressurized steam and uses it to do mechanical work on a rotating output shaft. Its modern manifestation was invented by Charles Parsons in 1884. Fabrication of a modern steam turbin ...

s, each driving one shaft, using steam from eight Admiralty 3-drum boilers. The turbines were rated at and intended to give the ship a maximum speed of 23 knots. During her sea trial

A sea trial is the testing phase of a watercraft (including boats, ships, and submarines). It is also referred to as a " shakedown cruise" by many naval personnel. It is usually the last phase of construction and takes place on open water, and ...

s on 7 September 1927, ''Rodney'' reached a top speed of from . The ship carried enough fuel oil

Fuel oil is any of various fractions obtained from the distillation of petroleum (crude oil). Such oils include distillates (the lighter fractions) and residues (the heavier fractions). Fuel oils include heavy fuel oil, marine fuel oil (MFO), bun ...

to give her a range of at a cruising speed of .

Armament and fire control

The

The main battery

A main battery is the primary weapon or group of weapons around which a warship is designed. As such, a main battery was historically a gun or group of guns, as in the broadsides of cannon on a ship of the line. Later, this came to be turreted ...

of the ''Nelson''-class ships consisted of nine breech-loading

A breechloader is a firearm in which the user loads the ammunition (cartridge or shell) via the rear (breech) end of its barrel, as opposed to a muzzleloader, which loads ammunition via the front ( muzzle).

Modern firearms are generally breech ...

(BL) guns in three triple-gun turret

A gun turret (or simply turret) is a mounting platform from which weapons can be fired that affords protection, visibility and ability to turn and aim. A modern gun turret is generally a rotatable weapon mount that houses the crew or mechani ...

s forward of the superstructure

A superstructure is an upward extension of an existing structure above a baseline. This term is applied to various kinds of physical structures such as buildings, bridges, or ships.

Aboard ships and large boats

On water craft, the superstruct ...

. Designated 'A', 'B' and 'X' from front to rear, 'B' turret superfired over the others. Their secondary armament

Secondary armament is a term used to refer to smaller, faster-firing weapons that were typically effective at a shorter range than the main (heavy) weapons on military systems, including battleship- and cruiser-type warships, tanks/armored ...

consisted of a dozen BL Mk XXII guns in twin-gun turrets aft of the superstructure, three turrets on each broadside

Broadside or broadsides may refer to:

Naval

* Broadside (naval), terminology for the side of a ship, the battery of cannon on one side of a warship, or their near simultaneous fire on naval warfare

Printing and literature

* Broadside (comic ...

. Their anti-aircraft

Anti-aircraft warfare, counter-air or air defence forces is the battlespace response to aerial warfare, defined by NATO as "all measures designed to nullify or reduce the effectiveness of hostile air action".AAP-6 It includes surface based, ...

(AA) armament consisted of six quick-firing (QF) Mk VIII guns in unshielded single mounts and eight QF 2-pounder () guns in single mounts. The ships were fitted with two submerged 24.5-inch (622 mm) torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed aboa ...

s, one on each broadside, angled 10° off the centreline.

The ''Nelson''s were built with two fire-control directors fitted with rangefinder

A rangefinder (also rangefinding telemeter, depending on the context) is a device used to measure distances to remote objects. Originally optical devices used in surveying, they soon found applications in other fields, such as photography an ...

s. One was mounted above the bridge

A bridge is a structure built to span a physical obstacle (such as a body of water, valley, road, or rail) without blocking the way underneath. It is constructed for the purpose of providing passage over the obstacle, which is usually somethi ...

and the other was at the aft end of the superstructure. Each turret was also fitted with a rangefinder. The secondary armament was controlled by four directors equipped with rangefinders. One pair were mounted on each side of the main director on the bridge roof and the others were abreast the aft main director. The anti-aircraft directors were situated on a tower abaft the main-armament director with a 12-foot high-angle rangefinder in the middle of the tower. A pair of torpedo-control directors with 15-foot rangefinders were positioned abreast the funnel

A funnel is a tube or pipe that is wide at the top and narrow at the bottom, used for guiding liquid or powder into a small opening.

Funnels are usually made of stainless steel, aluminium, glass, or plastic. The material used in its construct ...

.

Protection

The ships' waterline belt consisted ofKrupp cemented armour

Krupp armour was a type of steel naval armour used in the construction of capital ships starting shortly before the end of the nineteenth century. It was developed by Germany's Krupp Arms Works in 1893 and quickly replaced Harvey armour as the pr ...

(KC) that was thick between the main gun barbette

Barbettes are several types of gun emplacement in terrestrial fortifications or on naval ships.

In recent naval usage, a barbette is a protective circular armour support for a heavy gun turret. This evolved from earlier forms of gun protection ...

s and thinned to over the engine

An engine or motor is a machine designed to convert one or more forms of energy into mechanical energy.

Available energy sources include potential energy (e.g. energy of the Earth's gravitational field as exploited in hydroelectric power gen ...

and boiler rooms as well as the six-inch magazines

A magazine is a periodical publication, generally published on a regular schedule (often weekly or monthly), containing a variety of content. They are generally financed by advertising, purchase price, prepaid subscriptions, or by a combination ...

, but did not reach either the bow or the stern. To improve its ability to deflect plunging fire, its upper edge was inclined 18° outward. The ends of the armoured citadel were closed off by transverse bulkheads of non-cemented armour thick at the forward end and thick at the aft end. The faces of the main-gun turrets were protected by 16-inch of KC armour while the turret sides were thick and the roof armour plates measured in thickness. The KC armour of the barbettes ranged in thickness from .Raven & Roberts, pp. 114, 123

The top of the armoured citadel of the ''Nelson''-class ships was protected by an armoured deck that rested on the top of the belt armour. Its non-cemented armour plates ranged in thickness from over the main-gun magazines to over the propulsion machinery spaces and the secondary magazines. Aft of the citadel was an armoured deck thick at the level of the lower edge of the belt armour that extended almost to the end of the stern

The stern is the back or aft-most part of a ship or boat, technically defined as the area built up over the sternpost, extending upwards from the counter rail to the taffrail. The stern lies opposite the bow, the foremost part of a ship. Ori ...

to cover the steering gear. The conning tower

A conning tower is a raised platform on a ship or submarine, often armored, from which an officer in charge can conn the vessel, controlling movements of the ship by giving orders to those responsible for the ship's engine, rudder, lines, and gro ...

's KC armour was thick with a roof. The secondary-gun turrets were protected by of non-cemented armour.

Underwater protection for the ''Nelson''s was provided by a double bottom deep and a torpedo protection system. It consisted of an empty outer watertight compartment

A compartment is a portion of the space within a ship defined vertically between decks and horizontally between bulkheads. It is analogous to a room within a building, and may provide watertight subdivision of the ship's hull important in retaini ...

and an inner water-filled compartment. They had a total depth of and were backed by a torpedo bulkhead

A torpedo bulkhead is a type of naval armour common on the more heavily armored warships, especially battleships and battlecruisers of the early 20th century. It is designed to keep the ship afloat even if the hull is struck underneath the belt ar ...

1.5 inches thick.

Design deficiencies

The ''Nelson'' class was an innovative design, but limited by the constraints of the Washington Naval Treaty. The decision to use 16-inch guns combined with the 35,000-ton displacement limit made saving weight the primary concern of designers. TheDirector of Naval Construction

The Director of Naval Construction (DNC) also known as the Department of the Director of Naval Construction and Directorate of Naval Construction and originally known as the Chief Constructor of the Navy was a senior principal civil officer resp ...

, Eustace Tennyson d'Eyncourt

Sir Eustace Henry William Tennyson d'Eyncourt, 1st Baronet (1 April 1868 – 1 February 1951) was a British naval architect and engineer. As Director of Naval Construction for the Royal Navy, 1912–1924, he was responsible for the design a ...

, informed the ship's designer, Edward Attwood, "In order to keep the displacement to 35,000 tons, everything is to be cut down to a minimum." The emphasis on saving weight resulted in deficiencies which affected the performance of ''Rodney'' during the Second World War. The design compromises had less negative consequences for ''Nelson'' because that ship underwent a number of refits immediately before and during the war. Naval architect This is the top category for all articles related to architecture and its practitioners.

{{Commons category, Architecture occupations

Design occupations

Architecture, Occupations ...

and historian David K. Brown stated, "It seems likely that in the quest for weight saving, the structure was not quite strong enough." Unlike ''Nelson'', which exceeded the design specification for machinery weight, the lighter machinery of ''Rodney'' resulted in chronic problems. The ship's endurance declined substantially in the decade after her launch; in her 1941 action against ''Bismarck'', ''Rodney'' was nearly forced to abandon the pursuit because of a lack of fuel. British designers cited the poor endurance of the ship when establishing the endurance requirements for the battleship . Throughout the war ''Rodney'' was plagued with leaks as a result of panting, and the ship required repairs because of serious leaks in 1940, 1941 and 1944. During one storm, the leaking was severe enough to overwhelm a 50-ton pump. Leaks, defective riveting, and other problems continued to affect ''Rodney'' even after a 1941 refit in Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

, Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

. By 1943 officials concluded that she required a complete modernization to extend her service life. The ship never received the necessary upgrades and as a result was unfit for service by the end of 1944.

Modifications

The high-angle directors and rangefinder and their platform were replaced by a new circular platform for the

The high-angle directors and rangefinder and their platform were replaced by a new circular platform for the High Angle Control System

High Angle Control System (HACS) was a British anti-aircraft fire-control system employed by the Royal Navy from 1931 and used widely during World War II. HACS calculated the necessary deflection required to place an explosive shell in the loc ...

(HACS) Mk I director by March 1930. By July 1932, the single two-pounder guns and the starboard torpedo director were removed and replaced by a single octuple two-pounder "pom-pom" mount on the starboard

Port and starboard are nautical terms for watercraft and aircraft, referring respectively to the left and right sides of the vessel, when aboard and facing the bow (front).

Vessels with bilateral symmetry have left and right halves which are ...

side of the funnel and a rangefinder was added at the rear of the bridge roof. The port side mount was installed several years later in the position occupied by the port torpedo director and anti-aircraft directors for both mounts were added to the bridge structure. In 1934–1935, ''Rodney'' was fitted with a pair of quadruple mounts for Vickers

Vickers was a British engineering company that existed from 1828 until 1999. It was formed in Sheffield as a steel foundry by Edward Vickers and his father-in-law, and soon became famous for casting church bells. The company went public in 18 ...

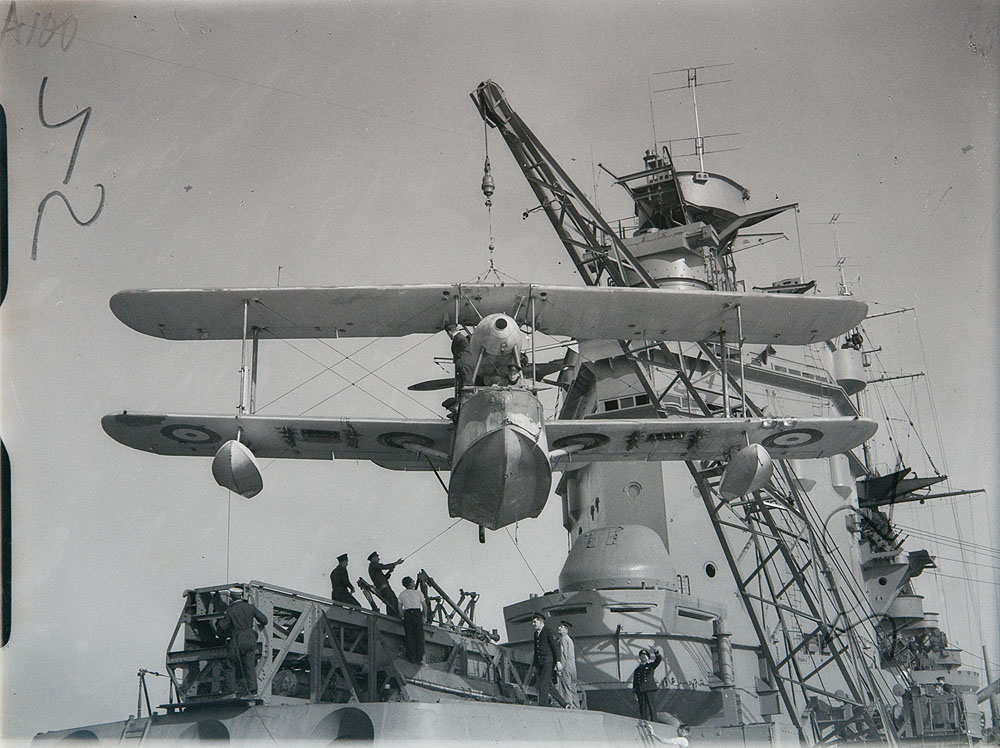

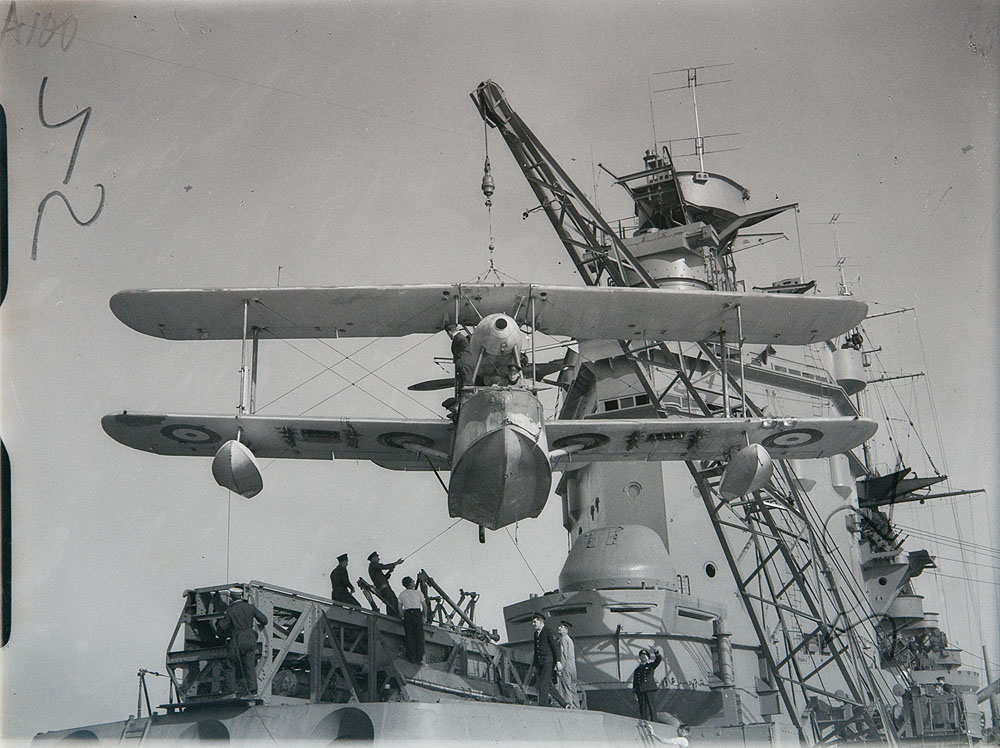

AA machineguns that were positioned on the forward superstructure. The ship was fitted with an aircraft catapult

An aircraft catapult is a device used to allow aircraft to take off from a very limited amount of space, such as the deck of a vessel, but can also be installed on land-based runways in rare cases. It is now most commonly used on aircraft carrier ...

on the roof of 'X' turret and a collapsible crane abreast the bridge was also added in 1937 to hoist the aircraft in and out of the water. A floatplane

A floatplane is a type of seaplane with one or more slender floats mounted under the fuselage to provide buoyancy. By contrast, a flying boat uses its fuselage for buoyancy. Either type of seaplane may also have landing gear suitable for land, ...

version of the Fairey Swordfish

The Fairey Swordfish is a biplane torpedo bomber, designed by the Fairey Aviation Company. Originating in the early 1930s, the Swordfish, nicknamed "Stringbag", was principally operated by the Fleet Air Arm of the Royal Navy. It was also used ...

torpedo bomber

A torpedo bomber is a military aircraft designed primarily to attack ships with aerial torpedoes. Torpedo bombers came into existence just before the First World War almost as soon as aircraft were built that were capable of carrying the weight ...

was first used aboard, but it was soon replaced by a Supermarine Walrus

The Supermarine Walrus (originally designated the Supermarine Seagull V) was a British single-engine amphibious biplane reconnaissance aircraft designed by R. J. Mitchell and manufactured by Supermarine at Woolston, Southampton.

The Walrus f ...

amphibian

Amphibians are tetrapod, four-limbed and ectothermic vertebrates of the Class (biology), class Amphibia. All living amphibians belong to the group Lissamphibia. They inhabit a wide variety of habitats, with most species living within terres ...

. In October 1938 another octuple "pom-pom" mount was added on the quarterdeck and a prototype Type 79Y early-warning radar

An early-warning radar is any radar system used primarily for the long-range detection of its targets, i.e., allowing defences to be alerted as ''early'' as possible before the intruder reaches its target, giving the air defences the maximum t ...

system was installed on ''Rodney''s masthead. She was the first battleship to be so equipped.

During a brief refit in HM Dockyard, Rosyth, Scotland, from 24 August to 10 September 1940, the Type 79Y radar was upgraded to a Type 279 system and two Oerlikon light

During a brief refit in HM Dockyard, Rosyth, Scotland, from 24 August to 10 September 1940, the Type 79Y radar was upgraded to a Type 279 system and two Oerlikon light AA gun

Anti-aircraft warfare, counter-air or air defence forces is the battlespace response to aerial warfare, defined by NATO as "all measures designed to nullify or reduce the effectiveness of hostile air action".AAP-6 It includes surface based, ...

s were installed on the roof of 'B' turret. While ''Rodney'' was refitting in the Boston Navy Yard

The Boston Navy Yard, originally called the Charlestown Navy Yard and later Boston Naval Shipyard, was one of the oldest shipbuilding facilities in the United States Navy. It was established in 1801 as part of the recent establishment of t ...

in the United States in June–August 1941, the Oerlikons were replaced by a quadruple two-pounder mount and a pair of octuple two-pounder mounts were fitted in lieu of the aft six-inch gunnery directors. In addition a full suite of radars were added. A Type 281 radar

The Type 281 radar was a British naval early-warning radar developed during World War II. It replaced the Type 79 as the Royal Navy's main early-warning radar during the war.

The prototype system was mounted on the light cruiser in October 1 ...

replaced the Type 279, a Type 271 surface-search radar This is a list of different types of radar.

Detection and search radars

Search radars scan great volumes of space with pulses of short radio waves. They typically scan the volume two to four times a minute. The waves are usually less than a meter ...

was installed as was a Type 284 gunnery radar on the roof of the forward main-gun director. The ship's light AA armament was heavily reinforced during a refit in February–May 1942 with seventeen 20 mm Oerlikons in single mounts added to turret roofs, the superstructure and the decks. The quadruple 0.5-inch mounts were replaced with Mk III "pom-pom" directors and three additional Mk IIIs were installed to control the aft octuple two-pounder mounts, all of which were fitted with Type 282 fire-control radars. The HACS Mk I was replaced by a Mk III director and four barrage (anti-aircraft) directors with Type 283 radars were added for the main guns. In addition her radar suite was upgraded: the Type 271 radar was replaced by a Type 273 system, a Type 291 early-warning radar was added and a Type 285 fire-control radar was installed on the roof of the HACS director.

While under repair at Rosyth in August–September, four additional Oerlikons were added on the quarterdeck. In May 1943 gun shield

A U.S. Marine manning an M240 machine gun equipped with a gun shield

A gun shield is a flat (or sometimes curved) piece of armor designed to be mounted on a crew-served weapon such as a machine gun, automatic grenade launcher, or artillery piece ...

s were added to the 4.7-inch guns and the catapult on the roof of 'X' turret was removed. Many more Oerlikons were installed during this brief refit, specifically 36 more single mounts and 5 twin mounts, which gave ''Rodney'' a total of 67 weapons in 57 single and 5 twin mounts. In preparation for her role providing naval gunfire support during the Normandy landings, two more Oerlikons were added as was a Type 650 radio jammer in January–March 1944. These additions increased the ship's deep displacement to and her crew to 1,631–1,650 men.

Construction and career

''Rodney'', named for

''Rodney'', named for Admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet, ...

Lord George Rodney, was the sixth ship of her name to serve in the Royal Navy. Given the yard number

__NOTOC__

M

...

904, she was laid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one o ...

on 28 December 1922 as part of the 1922 Naval Programme at Cammell Laird

Cammell Laird is a British shipbuilding company. It was formed from the merger of Laird Brothers of Birkenhead and Johnson Cammell & Co of Sheffield at the turn of the twentieth century. The company also built railway rolling stock until 1929, ...

's shipyard

A shipyard, also called a dockyard or boatyard, is a place where ships are built and repaired. These can be yachts, military vessels, cruise liners or other cargo or passenger ships. Dockyards are sometimes more associated with maintenance a ...

in Birkenhead

Birkenhead (; cy, Penbedw) is a town in the Metropolitan Borough of Wirral, Merseyside, England; historically, it was part of Cheshire until 1974. The town is on the Wirral Peninsula, along the south bank of the River Mersey, opposite Liver ...

Burt, p. 382 and was launched on 17 December 1925 by Princess Mary, Viscountess Lascelles, after three attempts at cracking the bottle of Imperial Burgundy. She was completed and her trials began in August 1927 and she was commissioned on 7 December under the command of Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

Henry Kitson

Vice Admiral Sir Henry Karslake Kitson KBE, CB (22 June 1877 – 19 February 1952) was a Royal Navy officer who commanded the 3rd Battle Squadron.

Naval career

Kitson joined the Royal Navy in 1891 and served in World War I. He was made Co ...

. The ship cost £7,617,799. The ''Nelson''-class ships received several nicknames: ''Rodnol'' and ''Nelsol'' after the Royal Fleet Auxiliary

The Royal Fleet Auxiliary (RFA) is a naval auxiliary fleet owned by the UK's Ministry of Defence. It provides logistical and operational support to the Royal Navy and Royal Marines. The RFA ensures the Royal Navy is supplied and supported by ...

oil tanker

An oil tanker, also known as a petroleum tanker, is a ship designed for the bulk transport of oil or its products. There are two basic types of oil tankers: crude tankers and product tankers. Crude tankers move large quantities of unrefined crud ...

s with a prominent amidships superstructure and names ending in "ol", ''The Queen's Mansions'' after a resemblance between her superstructure and the Queen Anne's Mansions

Queen Anne's Mansions was a block of flats in Petty France, Westminster, London, at . In 1873, Henry Alers Hankey acquired a site between St James's Park and St James's Park Underground station. Acting as his own architect, and employing his ...

block of flats

An apartment (American English), or flat (British English, Indian English, South African English), is a self-contained housing unit (a type of residential real estate) that occupies part of a building, generally on a single story. There are man ...

, the ''pair of boot'', the ''ugly sisters'' and the ''Cherry Tree class'' as they were cut-down by the Washington Naval Treaty. ''Rodney''s trials resumed after she was formally commissioned and continued until she entered service on 28 March 1928. The ship was assigned to the 2nd Battle Squadron of the Atlantic Fleet (renamed as Home Fleet in March 1932) and remained so, aside from refits or repairs, until 1941. On 21 April, Kitson was relieved by Captain Francis Tottenham. The following month she headed north to Invergordon

Invergordon (; gd, Inbhir Ghòrdain or ) is a town and port in Easter Ross, in Ross and Cromarty, Highland (council area), Highland, Scotland. It lies in the parish of Rosskeen.

History

The town built up around the harbour which was establish ...

, Scotland, to join the rest of the Atlantic Fleet in the annual exercises. ''Rodney'' returned to the south in August, where she was the Royal Guardship

A guard ship is a warship assigned as a stationary guard in a port or harbour, as opposed to a coastal patrol boat, which serves its protective role at sea.

Royal Navy

In the Royal Navy of the eighteenth century, peacetime guard ships were usual ...

during Cowes Week

Cowes Week ( ) is one of the longest-running regular regattas in the world. With 40 daily sailing races, up to 1,000 boats, and 8,000 competitors ranging from Olympic and world-class professionals to weekend sailors, it is the largest saili ...

where the ship hosted King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until Death and state funeral of George V, his death in 1936.

Born duri ...

and Queen Mary of Teck

Mary of Teck (Victoria Mary Augusta Louise Olga Pauline Claudine Agnes; 26 May 186724 March 1953) was Queen of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Empress of India, from 6 May 1910 until 20 January 1936 as the wife of King-Empe ...

on 11 August. The battleship then sailed to HM Dockyard, Devonport, to participate in a charity fund-raising Navy Week which saw 67,000 visitors come to the dockyard. ''Rodney'' had some work done on her hull in Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

's Gladstone Dock

Gladstone Dock is a dock on the River Mersey, England, and part of the Port of Liverpool. It is situated in the northern dock system in Bootle. The dock is connected to Seaforth Dock to the north and what remains of Hornby Dock to the south. P ...

in early October.

At the beginning of 1929, the Atlantic and Mediterranean Fleet

The British Mediterranean Fleet, also known as the Mediterranean Station, was a formation of the Royal Navy. The Fleet was one of the most prestigious commands in the navy for the majority of its history, defending the vital sea link between t ...

s combined for their annual fleet manoeuvres in the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ea ...

. While visiting Torquay

Torquay ( ) is a seaside town in Devon, England, part of the unitary authority area of Torbay. It lies south of the county town of Exeter and east-north-east of Plymouth, on the north of Tor Bay, adjoining the neighbouring town of Paignton ...

, Devon

Devon ( , historically known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South West England. The most populous settlement in Devon is the city of Plymouth, followed by Devon's county town, the city of Exeter. Devon is ...

, for a fleet rendezvous in July, ''Rodney'' was ordered to go to the assistance of two submarines that had collided off Milford Haven

Milford Haven ( cy, Aberdaugleddau, meaning "mouth of the two Rivers Cleddau") is both a town and a community in Pembrokeshire, Wales. It is situated on the north side of the Milford Haven Waterway, an estuary forming a natural harbour that has ...

, Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the Wales–England border, east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the ...

, on 9 July. Ordered to steam at full speed, the ship arrived at Pembroke Dock

Pembroke Dock ( cy, Doc Penfro) is a town and a community in Pembrokeshire, South West Wales, northwest of Pembroke on the banks of the River Cleddau. Originally Paterchurch, a small fishing village, Pembroke Dock town expanded rapidly following ...

the following morning to load rescue and salvage equipment. Delayed for a day by weather too bad for diving, she arrived at the site the following evening but it was too late for any survivors of and ''Rodney'' set sail for HM Dockyard, Portsmouth

His Majesty's Naval Base, Portsmouth (HMNB Portsmouth) is one of three operating bases in the United Kingdom for the Royal Navy (the others being HMNB Clyde and HMNB Devonport). Portsmouth Naval Base is part of the city of Portsmouth; it is l ...

. The ship's propulsion machinery was proving troublesome by this time and she was docked there in late September for a refit that took the rest of the year. Captain Andrew Cunningham, later First Sea Lord

The First Sea Lord and Chief of the Naval Staff (1SL/CNS) is the military head of the Royal Navy and Naval Service of the United Kingdom. The First Sea Lord is usually the highest ranking and most senior admiral to serve in the British Armed ...

, relieved Tottenham on 15 December.

Aside from the usual schedule of exercises, 1930 saw ''Rodney'' visit Portrush

Portrush () is a small seaside resort town on the north coast of County Antrim, Northern Ireland. It neighbours the resort of Portstewart. The main part of the old town, including the railway station as well as most hotels, restaurants and bars, ...

, Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. Nort ...

in June, which named a street after the battleship and a voyage to Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its s ...

to commemorate the thousandth year of the Icelandic Parliament

The Alþingi (''general meeting'' in Icelandic, , anglicised as ' or ') is the supreme national parliament of Iceland. It is one of the oldest surviving parliaments in the world. The Althing was founded in 930 at ("thing fields" or "assembl ...

. Cunningham was relieved by Captain Roger Bellairs on 16 December. In mid-September 1931, the crew of ''Rodney'' took part in the Invergordon Mutiny

The Invergordon Mutiny was an industrial action by around 1,000 sailors in the British Atlantic Fleet that took place on 15–16 September 1931. For two days, ships of the Royal Navy at Invergordon were in open mutiny, in one of the few mili ...

when they refused orders to go to sea for an exercise, although they relented after several days when the Admiralty reduced the severity of the pay cuts that prompted the mutiny. Unhappy with how Bellairs had handled the crew during the mutiny, the Admiralty ordered that he was to be relieved by Captain John Tovey

Admiral of the Fleet John Cronyn Tovey, 1st Baron Tovey, (7 March 1885 – 12 January 1971), sometimes known as Jack Tovey, was a Royal Navy officer. During the First World War he commanded the destroyer at the Battle of Jutland and then co ...

on 12 April 1932.

After ''Nelson'' ran aground while leaving Portsmouth in January 1934, ''Rodney'' became the temporary fleet flagship when Admiral Lord William Boyle, commander of the Home Fleet, hoisted his flag aboard her for the winter cruise to the British West Indies

The British West Indies (BWI) were colonized British territories in the West Indies: Anguilla, the Cayman Islands, Turks and Caicos Islands, Montserrat, the British Virgin Islands, Antigua and Barbuda, The Bahamas, Barbados, Dominica, Grena ...

. The fleet visited two Norwegian

Norwegian, Norwayan, or Norsk may refer to:

*Something of, from, or related to Norway, a country in northwestern Europe

* Norwegians, both a nation and an ethnic group native to Norway

* Demographics of Norway

*The Norwegian language, including ...

ports before returning home. Captain Wilfred Custance

Rear Admiral Wilfred Neville Custance CB (25 June 1884 – 13 December 1939) was a senior officer in the Royal Navy. He was the Rear Admiral Commanding HM Australian Squadron from April 1938 to September 1939.

Naval career

Born on 25 June 188 ...

relieved Tovey on 31 August. The 1935 winter cruise saw the ship return to the West Indies, before visiting the Azores

)

, motto =( en, "Rather die free than subjected in peace")

, anthem= ( en, "Anthem of the Azores")

, image_map=Locator_map_of_Azores_in_EU.svg

, map_alt=Location of the Azores within the European Union

, map_caption=Location of the Azores wi ...

and then Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

between 15 January and 17 March. The ship participated in King George V's Silver Jubilee Fleet Review

A fleet review or naval review is an event where a gathering of ships from a particular navy is paraded and reviewed by an incumbent head of state and/or other official civilian and military dignitaries. A number of national navies continue to ...

at Spithead

Spithead is an area of the Solent and a roadstead off Gilkicker Point in Hampshire, England. It is protected from all winds except those from the southeast. It receives its name from the Spit, a sandbank stretching south from the Hampshire ...

on 16 July and then again served as the Royal Guardship during Cowes Week. Captain William Whitworth William Whitworth may refer to:

* Sir William Whitworth (Royal Navy officer) (1884–1973)

* William Whitworth (journalist) (born 1937), American journalist and editor

* William Whitworth (politician) (1813–1886), British cotton manufacturer and ...

replaced Custance on 21 February 1936 and he was relieved in his turn by Captain Ronald Halifax on 25 July.

Some of ''Rodney''s crew travelled to London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

to participate in King George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death in 1952. He was also the last Emperor of Ind ...

's Coronation on 12 May 1937 and the ship took part in the Fleet Review at Spithead on 20 May. She again became the temporary fleet flagship when ''Nelson'' began a lengthy refit the following month and Admiral Sir Roger Backhouse

Admiral of the Fleet Sir Roger Roland Charles Backhouse, (24 November 1878 – 15 July 1939) was a Royal Navy officer. He served in the First World War as a cruiser commander and after the war became a battle squadron commander and later Com ...

hoisted his flag aboard her. ''Rodney'' visited Oslo

Oslo ( , , or ; sma, Oslove) is the capital and most populous city of Norway. It constitutes both a county and a municipality. The municipality of Oslo had a population of in 2022, while the city's greater urban area had a population of ...

, Norway, in July. ''Nelson''s refit ended in February 1938 and the sisters made a port visit to Lisbon

Lisbon (; pt, Lisboa ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 544,851 within its administrative limits in an area of 100.05 km2. Grande Lisboa, Lisbon's urban area extends beyond the city's administr ...

, Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

that same month. Captain Edward Syfret

Admiral Sir Edward Neville Syfret, (20 June 1889 – 10 December 1972) was a senior officer in the Royal Navy who saw service in both World Wars. He was knighted for his part in Operation Pedestal, the critical Malta convoy, in the Second World ...

relieved Whitworth on 16 August, shortly before ''Rodney'' began her annual short refit in September. After the completion of her post-refit trials in January 1939, Rear-Admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star "admiral" rank. It is often regarded ...

Lancelot Holland

Vice-Admiral Lancelot Ernest Holland, (13 September 1887 – 24 May 1941) was a Royal Navy officer who commanded the British force in the Battle of the Denmark Strait in May 1941 against the German battleship ''Bismarck''. Holland was lost ...

hoisted his flag aboard the ship as the commander of the 2nd Battle Squadron. She fired a 21-gun salute

A 21-gun salute is the most commonly recognized of the customary gun salutes that are performed by the firing of cannons or artillery as a military honor. As naval customs evolved, 21 guns came to be fired for heads of state, or in exceptiona ...

in honour of the French President

The president of France, officially the president of the French Republic (french: Président de la République française), is the executive head of state of France, and the commander-in-chief of the French Armed Forces. As the presidency is ...

Albert Lebrun

Albert François Lebrun (; 29 August 1871 – 6 March 1950) was a French politician, President of France from 1932 to 1940. He was the last president of the Third Republic. He was a member of the centre-right Democratic Republican Alliance (AR ...

's arrival in Dover

Dover () is a town and major ferry port in Kent, South East England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies south-east of Canterbury and east of Maidstone ...

in March for talks with the British government. As the Home Fleet was assembling in Scapa Flow

Scapa Flow viewed from its eastern end in June 2009

Scapa Flow (; ) is a body of water in the Orkney Islands, Scotland, sheltered by the islands of Mainland, Graemsay, Burray,S. C. George, ''Jutland to Junkyard'', 1973. South Ronaldsay and ...

when tensions with Germany rose in August, ''Rodney'' developed steering problems and had to proceed to Rosyth

Rosyth ( gd, Ros Fhìobh, "headland of Fife") is a town on the Firth of Forth, south of the centre of Dunfermline. According to the census of 2011, the town has a population of 13,440.

The new town was founded as a Garden city-style suburb ...

for repairs and a bottom cleaning.

Second World War

1939

When Great Britain declared war on Nazi Germany on 3 September 1939, ''Rodney'' and the bulk of the Home Fleet were patrolling the waters between Iceland, Norway and Scotland for Germanblockade runner

A blockade runner is a merchant vessel used for evading a naval blockade of a port or strait. It is usually light and fast, using stealth and speed rather than confronting the blockaders in order to break the blockade. Blockade runners usuall ...

s and then did much the same off the Norwegian coast from 6 to 10 September. The Home Fleet was already at sea when the submarine , on patrol in the Heligoland Bight

The Heligoland Bight, also known as Helgoland Bight, (german: Helgoländer Bucht) is a bay which forms the southern part of the German Bight, itself a bay of the North Sea, located at the mouth of the Elbe river. The Heligoland Bight extends fro ...

, was badly damaged by German depth charge

A depth charge is an anti-submarine warfare (ASW) weapon. It is intended to destroy a submarine by being dropped into the water nearby and detonating, subjecting the target to a powerful and destructive Shock factor, hydraulic shock. Most depth ...

s on 24 September. Unable to submerge, she requested assistance and the fleet responded with two destroyers

In navy, naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a Naval fleet, fleet, convoy or Carrier battle group, battle group and defend them against powerful short range attack ...

escorting her home and the balance of the fleet providing cover

Cover or covers may refer to:

Packaging

* Another name for a lid

* Cover (philately), generic term for envelope or package

* Album cover, the front of the packaging

* Book cover or magazine cover

** Book design

** Back cover copy, part of co ...

. The Germans spotted the bulk of the Home Fleet and it was attacked by five bombers from the first group

A group is a number of persons or things that are located, gathered, or classed together.

Groups of people

* Cultural group, a group whose members share the same cultural identity

* Ethnic group, a group whose members share the same ethnic ide ...

of Bomber Wing 30 (I./KG 30). ''Rodney''s radar provided timely warning and the aircraft inflicted no damage on the British ships. The following month the ship was part of the covering force for an iron ore

Iron ores are rocks and minerals from which metallic iron can be economically extracted. The ores are usually rich in iron oxides and vary in color from dark grey, bright yellow, or deep purple to rusty red. The iron is usually found in the fo ...

convoy from Narvik

( se, Áhkanjárga) is the third-largest municipality in Nordland county, Norway, by population. The administrative centre of the municipality is the town of Narvik. Some of the notable villages in the municipality include Ankenesstranda, Ball ...

, Norway.

Syfret was relieved by Captain Frederick Dalrymple-Hamilton

Admiral Sir Frederick Hew George Dalrymple-Hamilton KCB (27 March 1890 – 26 December 1974) was a British naval officer who served in World War I and World War II. He was captain of ''HMS Rodney'' when it engaged the ''Bismarck'' on 27 May ...

on 21 November. Following the sinking of the armed merchant cruiser

An armed merchantman is a merchant ship equipped with guns, usually for defensive purposes, either by design or after the fact. In the days of sail, piracy and privateers, many merchantmen would be routinely armed, especially those engaging in lo ...

two days later by the German battleships and off Iceland, ''Rodney'' and the rest of the Home Fleet were sent to look for them but heavy weather allowed the German battleships to evade their pursuers and return to Germany. The battleship developed serious problems with her rudder

A rudder is a primary control surface used to steer a ship, boat, submarine, hovercraft, aircraft, or other vehicle that moves through a fluid medium (generally aircraft, air or watercraft, water). On an aircraft the rudder is used primarily to ...

on 29 November and was forced to return to Liverpool, steering only with her engines, for repairs that lasted until 31 December.

1940

With ''Nelson'' damaged by a mine on 4 December, ''Rodney'' served as the temporary fleet flagship until her sister's return in August. She mostly spent January and February 1940 at anchor with occasional missions to provide cover from commerce raiders for convoys. During one such sortie on 21 February in heavy weather, her steering problems resurfaced and forced her return to

With ''Nelson'' damaged by a mine on 4 December, ''Rodney'' served as the temporary fleet flagship until her sister's return in August. She mostly spent January and February 1940 at anchor with occasional missions to provide cover from commerce raiders for convoys. During one such sortie on 21 February in heavy weather, her steering problems resurfaced and forced her return to Greenock

Greenock (; sco, Greenock; gd, Grianaig, ) is a town and administrative centre in the Inverclyde council areas of Scotland, council area in Scotland, United Kingdom and a former burgh of barony, burgh within the Counties of Scotland, historic ...

, Scotland. Six days later, the ship was visited by King George VI and Queen Elizabeth during their morale-boosting tour of Scottish shipyards. The Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

boarded ''Rodney'' for a voyage to Scapa Flow on 7 to 8 March. Despite the danger of aerial attack by the Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German ''Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the ''Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabtei ...

, most of the Home Fleet was now based there; ''Rodney'' was near-missed during an attack on 16 March.

Receiving word that the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

(RAF) had attacked north-bound German warships in the North Sea on 7 April, Admiral Sir Charles Forbes, Commander-in-chief Home Fleet, ordered most of his ships to put to sea that evening. ''Rodney'' was hit by a bomb on 9 April off the south-western coast of Norway. The bomb broke up after hitting the corner of a armoured 4.7-inch ready ammunition box on the upper deck aft of the funnel; its fragments penetrated through several decks before bouncing off the four-inch armoured deck and started a small fire in the galley

A galley is a type of ship that is propelled mainly by oars. The galley is characterized by its long, slender hull, shallow draft, and low freeboard (clearance between sea and gunwale). Virtually all types of galleys had sails that could be used ...

. Three men were wounded by the bomb and another fifteen suffered electrical burns when water being used to fight the fire poured onto a junction box

An electrical junction box (also known as a "jbox") is an enclosure housing electrical connections. Junction boxes protect the electrical connections from the weather, as well as protecting people from accidental electric shocks.

Construction

...

. The crew made temporary repairs and the ship remained at sea until she dropped anchor at Scapa Flow on 17 April. Upon receiving notice that German ships had been spotted in the Norwegian Sea

The Norwegian Sea ( no, Norskehavet; is, Noregshaf; fo, Norskahavið) is a marginal sea, grouped with either the Atlantic Ocean or the Arctic Ocean, northwest of Norway between the North Sea and the Greenland Sea, adjoining the Barents Sea to ...

on 9 June, Forbes ordered the Home Fleet, including ''Rodney'', to sea to protect troop convoys evacuating Allied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

forces from Norway.

''Nelson'' returned from the dockyard on 24 July and reassumed her role as the Home Fleet flagship. ''Rodney'' was transferred from Scapa Flow to Rosyth on 23 August with orders to attack the German invasion fleet in the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

when Operation Sealion

Operation Sea Lion, also written as Operation Sealion (german: Unternehmen Seelöwe), was Nazi Germany's code name for the plan for an invasion of the United Kingdom during the Battle of Britain in the Second World War. Following the Battle ...

began. She returned to Scapa on 4 November to begin convoy escort duty. After the armed merchant cruiser was sunk the following day by the heavy cruiser , the sisters were deployed to the Iceland–Faeroes

The Faroe Islands ( ), or simply the Faroes ( fo, Føroyar ; da, Færøerne ), are a North Atlantic island group and an autonomous territory of the Kingdom of Denmark.

They are located north-northwest of Scotland, and about halfway betwee ...

gap to block any attempts by the German cruiser to return home. The following month ''Rodney'' was detailed to rendezvous with Convoy HX 93 from Halifax, Nova Scotia

Halifax is the capital and largest municipality of the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, and the largest municipality in Atlantic Canada. As of the 2021 Census, the municipal population was 439,819, with 348,634 people in its urban area. The ...

, and escort it home. The ship encountered a strong storm with gale-force winds from 6 to 8 December that caused leaks in her hull plating with a moderate amount of flooding. Repairs at Rosyth began on 18 December that included structural reinforcement of the hull plating and general reinforcement of the forward hull structure.

1941

After finishing her refit on 13 January 1941, ''Rodney'' joined the hunt for ''Scharnhorst'' and ''Gneisenau'', without success and then escorted Convoy HX 108 from 12 to 23 February. On 16 March, the ship spotted the latter battleship while escorting Convoy HX 114 in theNorth Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the "Old World" of Africa, Europe and ...

; ''Gneisenau'' was rescuing survivors from the independently steaming reefer ship

A reefer ship is a refrigerated cargo ship typically used to transport perishable cargo, which require temperature-controlled handling, such as fruits, meat, vegetables, dairy products, and similar items.

Description

''Types of reefers:'' Re ...

, , when ''Rodney'' steamed over the horizon, silhouetted against the setting sun. Partially hidden behind the burning merchant ship, the gunnery officer estimated that the intermittently visible German ship was away, close to maximum range for ''Rodney''s guns. Dalyrmple-Hamilton declined to pursue ''Gneisenau'' when she turned away at her top speed of and was able to rescue 27 survivors and 2 dead seamen from one lifeboat

Lifeboat may refer to:

Rescue vessels

* Lifeboat (shipboard), a small craft aboard a ship to allow for emergency escape

* Lifeboat (rescue), a boat designed for sea rescues

* Airborne lifeboat, an air-dropped boat used to save downed airmen

...

before returning to her convoy. Troop Convoy TC 10 departed Halifax on 10 April with a strong escort that included ''Rodney''. While steaming in the River Clyde

The River Clyde ( gd, Abhainn Chluaidh, , sco, Clyde Watter, or ) is a river that flows into the Firth of Clyde in Scotland. It is the ninth-longest river in the United Kingdom, and the third-longest in Scotland. It runs through the major cit ...

on 19 April, the battleship accidentally rammed and sank the trawler ''Topaze''; only four survivors could be rescued by nearby destroyers.

''Bismarck''

On 22 May 1941, ''Rodney'' and four destroyers were part of the escort for theocean liner

An ocean liner is a passenger ship primarily used as a form of transportation across seas or oceans. Ocean liners may also carry cargo or mail, and may sometimes be used for other purposes (such as for pleasure cruises or as hospital ships).

Ca ...

as she set sail for Halifax. The battleship was scheduled to continue onwards to Boston for repairs and a refit. To this end, the ship carried some of the materials, such as boiler tubes and three octuple "pom-pom" mounts intended for use in her refit; other cargo included three or four crates of the Elgin Marbles

The Elgin Marbles (), also known as the Parthenon Marbles ( el, Γλυπτά του Παρθενώνα, lit. "sculptures of the Parthenon"), are a collection of Classical Greek marble sculptures made under the supervision of the architect and s ...

. She also carried 521 military passengers bound for Halifax, as well as an American assistant naval attaché

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and related functions. It include ...

conveying important documents back to the United States. ''Britannic'' was taking civilians to Canada and would be bringing Canadian troops and airmen back to Britain.

After ''Bismarck'' sank the battlecruiser

The battlecruiser (also written as battle cruiser or battle-cruiser) was a type of capital ship of the first half of the 20th century. These were similar in displacement, armament and cost to battleships, but differed in form and balance of attr ...

during the Battle of Denmark Strait

The Battle of the Denmark Strait was a naval engagement in the Second World War, which took place on 24 May 1941 between ships of the Royal Navy and the '' Kriegsmarine''. The British battleship and the battlecruiser fought the German battl ...

on the morning of 24 May, ''Rodney'' was ordered by the Admiralty to join in the pursuit of the German ship, leaving the destroyer to escort ''Britannic'' and taking , and with her in the search. After the heavy cruiser radioed that she had lost radar contact with the ''Bismarck'' at 04:01 on the morning of 25 May, Dalrymple-Hamilton, after consulting his senior officers and the American attaché, decided that the German ship was probably heading for Brest

Brest may refer to:

Places

*Brest, Belarus

**Brest Region

**Brest Airport

**Brest Fortress

* Brest, Kyustendil Province, Bulgaria

* Břest, Czech Republic

*Brest, France

** Arrondissement of Brest

**Brest Bretagne Airport

** Château de Brest

*Br ...

and so set course to the east to head her off, at some stages reaching twenty-two knots, which exceeded her then theoretical maximum speed by , although this caused several mechanical failures. Later that morning, Admiral Sir John Tovey in the battleship ordered all ships to head north west due to a misinterpreted signal from the Admiralty but Dalrymple-Hamilton knew that his ship was too slow to catch up to ''Bismarck'' if she was headed in that direction and disregarded Tovey's order. The Admiralty informed Dalrymple-Hamilton that they believed that ''Bismarck'' was probably headed to Brest or Saint Nazaire

Saint-Nazaire (; ; Gallo: ''Saint-Nazère/Saint-Nazaer'') is a commune in the Loire-Atlantique department in western France, in traditional Brittany.

The town has a major harbour on the right bank of the Loire estuary, near the Atlantic Ocean. ...

at 11:40. The captain subsequently altered course further south east to cover the approaches to Spanish ports where the German ship might intern herself but this was countermanded by an Admiralty order to turn north east at 14:30. Dalrymple-Hamilton continued south east for several more hours before he decided to obey the order at 16:20; during this time ''Bismarck'' passed his position just under the horizon, about away. Not having spotted the German ship by 21:00, Dalrymple-Hamilton decided to turn south-east again, heading directly for Brest.

''Bismarck'' was spotted by a RAF

''Bismarck'' was spotted by a RAF Consolidated PBY Catalina

The Consolidated PBY Catalina is a flying boat and amphibious aircraft that was produced in the 1930s and 1940s. In Canadian service it was known as the Canso. It was one of the most widely used seaplanes of World War II. Catalinas served w ...

flying boat

A flying boat is a type of fixed-winged seaplane with a hull, allowing it to land on water. It differs from a floatplane in that a flying boat's fuselage is purpose-designed for floatation and contains a hull, while floatplanes rely on fusela ...

at 10:35 on 26 May and the two battleships were able to join up as Tovey had realised his mistake and doubled back. Despite the heavy weather, the aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

launched her first attack, by 14 Swordfish torpedo bombers, against the German ship that afternoon. The pilots mistook the light cruiser for the ''Bismarck'' and attacked, although the cruiser was able to evade the six of eleven torpedoes dropped that did not detonate when they hit the sea due to faulty magnetic detonators. Around dusk, ''Ark Royal'' launched an attack by 15 Swordfish, whose torpedoes had been fitted with contact detonators. Despite the heavy anti-aircraft fire, the Swordfish hit ''Bismarck'' with three torpedoes. Two of them struck forward of the aft gun turrets and caused no significant damage; the last struck the stern, disabled the battleship's steering and caused her to significantly reduce speed. That evening Tovey detached ''Mashona'' and ''Somali'' to refuel and had ''Rodney'' fall in behind ''King George V'' for the battle against ''Bismarck''. Although his ships could catch the German ship that night now that her steering had been disabled and her engines damaged, Tovey decided to reduce speed to save fuel and wait until dawn to allow his ships the maximum amount of time in which to sink the German ship.

''Rodney'' spotted ''Bismarck'' at 08:44 on 27 May, one minute after ''King George V'' and was the first to open fire at a range of three minutes later with ''Bismarck'' replying at 08:49. The initial salvo

A salvo is the simultaneous discharge of artillery or firearms including the firing of guns either to hit a target or to perform a salute. As a tactic in warfare, the intent is to cripple an enemy in one blow and prevent them from fighting b ...

s from both ships were off but ''Rodney'' straddled her opponent with her third salvo and hit her twice with her fourth at 09:02, knocking out the forward superfiring turret, disabling the lower turret and severely damaging her bridge. In her turn, ''Bismarck'' scored no hits, although she managed to damage ''Rodney'' with shell splinters before her forward guns were knocked out. As the British ship manoeuvred to bring 'X' turret to bear while closing the distance, she exposed herself to fire from ''Bismarck''s aft turrets, which only managed to straddle ''Rodney''. As the range diminished, she began to fire torpedoes, although shock waves from near misses caused the door for her starboard tube to jam at 09:23. At 09:31, the ship blew off the left barrel of the ''Bismarck''s lower aft gun turret and started a fire inside the turret that forced its evacuation. Around this time the combined fire from ''Rodney'', ''King George V'' and the heavy cruiser

The heavy cruiser was a type of cruiser, a naval warship designed for long range and high speed, armed generally with naval guns of roughly 203 mm (8 inches) in caliber, whose design parameters were dictated by the Washington Naval Tr ...

s and knocked out all of ''Bismarck''s main guns. ''Rodney'' closed to point-blank range

Point-blank range is any distance over which a certain firearm can hit a target without the need to compensate for bullet drop, and can be adjusted over a wide range of distances by sighting in the firearm. If the bullet leaves the barrel para ...

and continued to engage, starting to fire full broadsides into ''Bismarck'' on a virtually flat trajectory, and added three more torpedoes at a range of beginning at 09:51; one of these malfunctioned but another may have struck ''Bismarck''. According to the naval historian Ludovic Kennedy

Sir Ludovic Henry Coverley Kennedy (3 November 191918 October 2009) was a Scottish journalist, broadcaster, humanist and author best known for re-examining cases such as the Lindbergh kidnapping and the murder convictions of Timothy Evans an ...

, who was present at the battle in ''Tartar'', "if true, his is

His or HIS may refer to:

Computing

* Hightech Information System, a Hong Kong graphics card company

* Honeywell Information Systems

* Hybrid intelligent system

* Microsoft Host Integration Server

Education

* Hangzhou International School, in ...

the only instance in history of one battleship torpedoing another."

''Rodney'' fired 378 sixteen-inch shells and 706 six-inch shells during the battle before Dalrymple-Hamilton ordered cease fire around 10:16, while ''Dorsetshire'' was then ordered to finish ''Bismarck'' off with torpedoes. Ironically, ''Rodney''s own main guns firing at low elevation

The elevation of a geographic location is its height above or below a fixed reference point, most commonly a reference geoid, a mathematical model of the Earth's sea level as an equipotential gravitational surface (see Geodetic datum § Vert ...

had damaged her more extensively than had ''Bismarck''. Deck plates around the main-gun turrets had been depressed by the effects of the guns' muzzle blast

A muzzle blast is an explosive shockwave created at the muzzle of a firearm during shooting. Before a projectile leaves the gun barrel, it obturates the bore and "plugs up" the pressurized gaseous products of the propellant combustion behind i ...

, and some of the structural members supporting them had cracked or buckled. Piping, urinal

A urinal (, ) is a sanitary plumbing fixture for urination only. Urinals are often provided in public toilets for male users in Western countries (less so in Muslim countries). They are usually used in a standing position. Urinals can be with ...

s and water mains had broken, while the shock of firing had loosened rivets and bolts in the hull plating, flooding various compartments. One gun in 'A' turret permanently broke down during the battle and two others in 'B' turret were temporarily disabled.

''Rodney'' and ''King George V'', running short on fuel, were ordered home and were ineffectually attacked by a pair of Luftwaffe bombers the next day. The former ship arrived at Greenock to replenish her ammunition, fuel and supplies on 29 May and departed for Halifax on 4 June together with the ocean liner , escorted by four destroyers. ''Rodney'' continued to the Boston Navy Yard for the delayed repairs to her propulsion machinery and her self-inflicted damage from the battle where she arrived on 12 June. Since the repairs took several months to complete, ''Rodney''s crew was furloughed to local Civilian Conservation Corps

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was a voluntary government work relief program that ran from 1933 to 1942 in the United States for unemployed, unmarried men ages 18–25 and eventually expanded to ages 17–28. The CCC was a major part of ...

camps for a fortnight

A fortnight is a unit of time equal to 14 days (two weeks). The word derives from the Old English term , meaning "" (or "fourteen days," since the Anglo-Saxons counted by nights).

Astronomy and tides

In astronomy, a ''lunar fortnight'' is h ...

. During the refit, Dalrymple-Hamilton was relieved by Captain James Rivett-Carnac

Sir James Rivett-Carnac, 1st Baronet (11 November 1784 – 28 January 1846) was an Indian-born British statesman and politician who served as Governor of the Bombay Presidency in British India from 1838 to 1841.

Career

Born in Bombay in 1784, ...

and ''Rodney'' departed Boston for Bermuda on 20 August to work up. The ship arrived in Gibraltar on 24 September to join Force H.

Force H and subsequent operations

''Rodney'' departed Gibraltar later that day to join her sister in escorting a convoy toMalta